Last updated on November 7th, 2023 at 11:08 pm

The following piece was originally featured on Dad Behavior, a personal blog by Twiniversity contributor Brian Sutch.

My boys and I are members of a very exclusive club: We’re all being treated for a congenital heart defect called Long QT Syndrome. LQTS is a heart rhythm disorder that can potentially cause fast, chaotic heartbeats, which could trigger a sudden fainting spell or seizure. In some cases, the erratic heartbeat can even cause sudden death. Only about one in 7,000 people have LQTS, but it’s nothing new in my family; we’ve been dealing with the symptoms for generations, though it was only in the past 15 years or so that we’ve understood the cause.

I was first diagnosed through genetic testing in early 2006, when I was 24 years old. I had never experienced a symptom — and still haven’t — but my family’s extensive history paints a pretty clear picture of why the testing was necessary. My dad’s immediate and extended families had been plagued for decades by unexplained seizures, blackouts, and worse. In 1980, his 13-year-old sister died suddenly after a seizure. It was attributed, unconvincingly, to epilepsy. In 1995, my dad died in his sleep at age 39. Again, no satisfactory explanation was ever given. Once the initial LQTS diagnoses were made in the early 2000s, everything started to make sense.

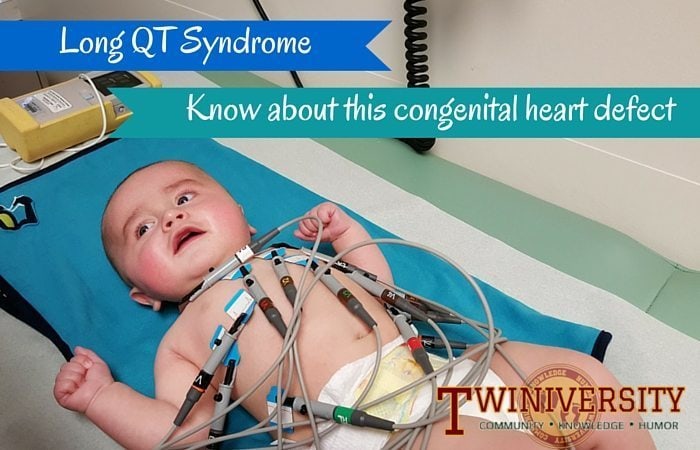

Inherited Long QT Syndrome (which can also be acquired through certain medications or underlying medical conditions) is an autosomal dominant disorder, which means if one parent has the abnormal gene, their child would have a 50% chance of inheriting it. We had my oldest son tested on the day he was born, in 2011, using blood drawn from his umbilical cord. When my twins were born last August, they each had several EKGs to catch any potential arrhythmias before they left the hospital, and were tested less than a week later. In all three cases, we started them on beta blockers preemptively while we awaited the genetic test results, which took about six to eight weeks.

Even though I knew the condition would be very manageable once diagnosed, I wasdisappointed when my older son tested positive. As any parent can attest, I wanted to guard him from anything that had even the slightest potential to do him harm. By the time we got the twins’ results back last fall, I fully expected both to be positive. After all, my dad’s offspring were batting 1.000 on this. He had it (we know this because it doesn’t skip a generation), I have it, my brother and sister both have it, and my oldest son has it. Two of my dad’s brothers and one sister have LQTS, and none have matched him in passing it on to every one of their kids.

That being the case, I was pretty shocked to learn that my girl twin had tested negative, finally breaking the chain in my immediate family. Her twin brother tested positive, unfortunately, but after having dealt with it for the last five years, my wife and I understand that, for us at least, treating LQTS is a small burden. That is not the case for every family, by any means, and some families learn about the condition only after it’s too late. The first symptom could be the last.

My boys each take a liquid beta blocker orally three times a day — they even take their 10 p.m. doses while asleep, which is a huge help. We take them to an excellent pediatric cardiologist (big Mets fan, by the way) at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in Queens, New York, every six months (every three months for the little guy, for now), where they get an EKG and a quick exam. This month they had their first joint appointment — an odd little way for brothers to bond, but the start of a tradition that could last a long time.

They’re both asymptomatic, though the potential is always there for that to change. While they don’t have any physical limitations right now, they could be restricted from playing certain sports — but, assuming they’re both blessed with their father’s complete lack of anything resembling athleticism, that may not be an issue. In time, they’ll take a daily tablet like I do, and when they’re older, the doctor may recommend an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), like the one I’ve had since 2006. Similar to a pacemaker, the ICD can monitor their heart rhythm to detect any potentially dangerous arrhythmias and shock them back to normal. I’ve had my share of problems with my ICD — a long story for another day — but I hope the medical device technology and progressive research of Long QT Syndrome and other heart rhythm disorders will yield a lot of positive results in the next decade.

I could go on about this for hours, but I’d rather just give you the basics here, in the hopes that I’ve raised a little bit of awareness. I want to encourage anyone reading this — parents especially — to educate yourselves about the warning signs of Long QT Syndrome and other sudden arrhythmia death syndromes (SADS). Please visit the SADS Foundation for more information, support, and resources for families and schools. Also, please feel free to get in touch with me on Twitter if you have any questions about this.

Brian Sutch is a stay-at-home-dad and a freelance writer/editor for Digital Trends, Kaplan, Along the Boards, and Triple Play Tribune. He blogs about his parental insecurities at DadBehavior.com when he’s not too busy with other stuff, and probably includes too many Game of Thrones and Simpsons references therein. His five 5-year-old son plans to explore outer space after his Hall of Fame baseball career. His infant twins (boy and girl) have not disclosed their career paths yet. You can find him on Twitter.